FREDERICK AND "THE GREAT WAR"

David John Markey (c. 1901)

David John Markey (c. 1901)

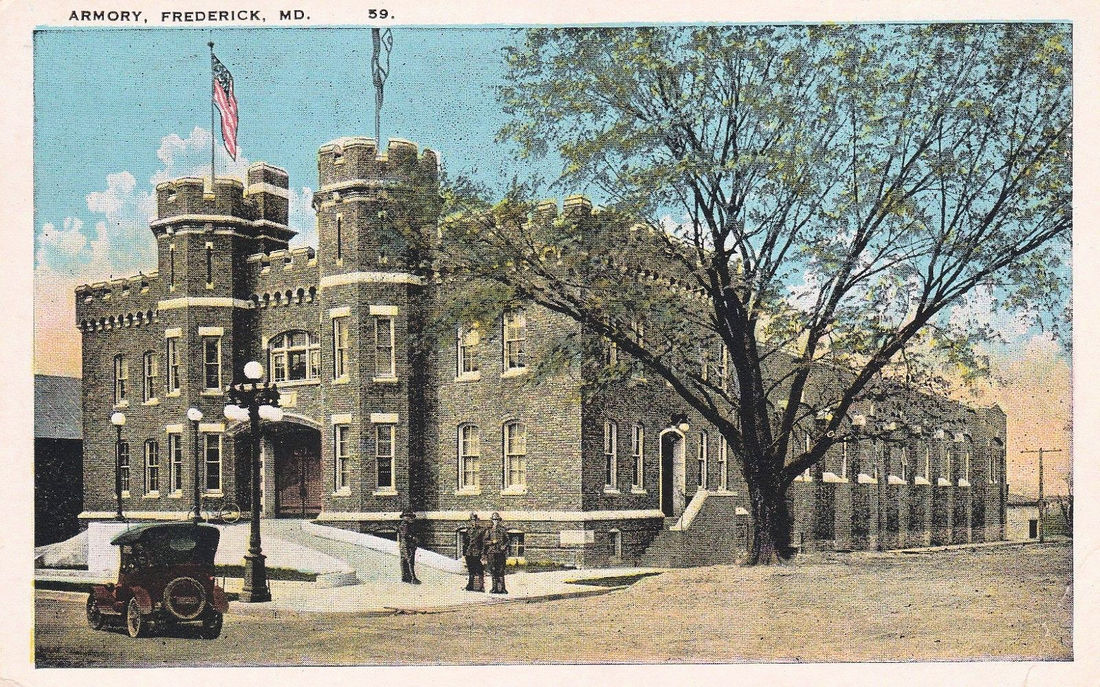

Before David John Markey opened his Frederick-based shoe and hat store, he coached the University of Maryland's football team for three seasons until 1903. Two years later, the local merchant decided to build another team under his leadership. Markey would organize Company A of Frederick and served as company captain of the local Maryland National Guard unit. Nearly ten years later in 1914, the second armory in the state outside Baltimore was built fronting on Bentz Street, near the site of the thoroughfare's namesake mill-the Bentz Mill. That same year, Captain Markey was promoted to major and became commander of the Western Maryland Battalion. To fill the vacancy left by Markey, Second Lieutenant Elmer F. Munshower, who enlisted as a private in 1906, was named captain and put in charge of the company unit.

It was also the year 1914 when war broke out in Serbia in Eastern Europe. Arch-duke Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary had been assassinated. Europe soon found itself engulfed in a war that would envelop the world. The people of Frederick County, like those of the rest of the nation, watched and listened as one European country after another was drawn into the conflict. America proclaimed neutrality, but in 1915 an event would occur on the high seas that would change this stance. The ship Lusitania containing many US passengers was sunk by a German submarine. By 1917, the Germans had destroyed three American ships. President Wilson and Congress declared war on Germany and its allies in April, 1917.

Frederick's origins were rooted in German culture, with many of its founding families being of German stock. These included Brunners, Schleys, Steiners and Ramsburgs to name a few. The town, and county, were named for an English prince with German ties, and the German language was commonly spoken here well into the late 1800's. Just 4-5 generations removed, and in some cases less, many residents had to come to grips with the enemy being Germany-distant relatives helped comprise the aggressors.

Just 50 years and two generations earlier, men had taken up arms in the American Civil War. Frederick had certainly seen its share of warfare and experienced the carnage brought with it. In many instances, neighbors took up arms against one another as Frederick County was "a border county within a border state." Now, all Frederick Countians were on the same team ,so to speak, as Americans against an aggressor comprised of the Central Powers including the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria. Most town and county residents proudly supported the war effort as we allied with a host of countries including past and future foes such as Great Britain, France, Italy, Russia and Japan.

Frederick's origins were rooted in German culture, with many of its founding families being of German stock. These included Brunners, Schleys, Steiners and Ramsburgs to name a few. The town, and county, were named for an English prince with German ties, and the German language was commonly spoken here well into the late 1800's. Just 4-5 generations removed, and in some cases less, many residents had to come to grips with the enemy being Germany-distant relatives helped comprise the aggressors.

Just 50 years and two generations earlier, men had taken up arms in the American Civil War. Frederick had certainly seen its share of warfare and experienced the carnage brought with it. In many instances, neighbors took up arms against one another as Frederick County was "a border county within a border state." Now, all Frederick Countians were on the same team ,so to speak, as Americans against an aggressor comprised of the Central Powers including the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria. Most town and county residents proudly supported the war effort as we allied with a host of countries including past and future foes such as Great Britain, France, Italy, Russia and Japan.

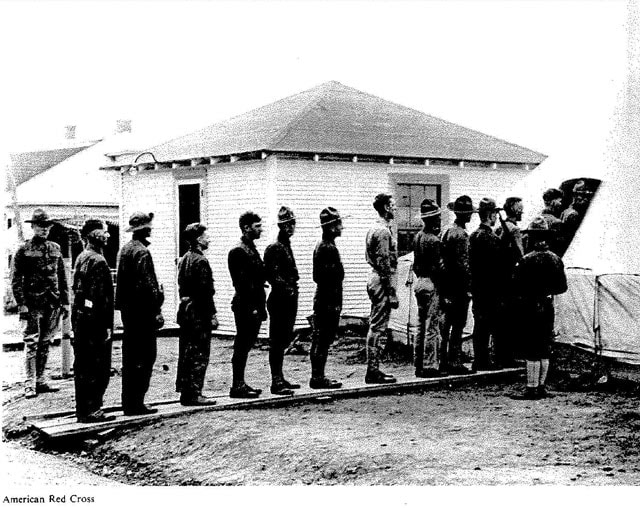

At this time, the only effective fighting forces in the United States were the National Guard units. Maryland had the 1st, 4th and 5th infantry regiments. Company A mobilized in the Frederick Armory and upped its ranks to 153 men through recruitment. The local unit eventually became part of the 115th Infantry Regiment. Frederick's Company A went to Camp McClellan, Alabama, where our local boys joined with units from the nation's capital, New Jersey, Delaware and Virginia to form the 29th Division. This group was also given the moniker of "the Blue and Gray Division" because it was made up of members from both north and south, a nod to the earlier "War between the States."

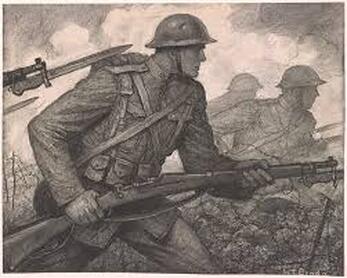

By July, 1918, these men had been fully trained, transported across the Atlantic to Europe, and were fighting on the front lines. The 115th distinguished itself as a brave fighting force in the Alsace Sector of France, followed by the Meuse-Argonne offensive which broke the Germans back, leading to victory for the Allied Expeditionary Forces. There was a cost however, as the 115th and its contingent of 3,834 men suffered 25% casualties. These soldiers were killed, wounded, gassed or went missing. Mount Olivet Cemetery is the final resting place of 12 known veterans who lost their lives in service connected deaths.

World War I officially ended on November 11th, 1918, known today as Armistice Day. When it was all said and done, almost 2,000 Frederick City residents had served their country in one way or another.

By July, 1918, these men had been fully trained, transported across the Atlantic to Europe, and were fighting on the front lines. The 115th distinguished itself as a brave fighting force in the Alsace Sector of France, followed by the Meuse-Argonne offensive which broke the Germans back, leading to victory for the Allied Expeditionary Forces. There was a cost however, as the 115th and its contingent of 3,834 men suffered 25% casualties. These soldiers were killed, wounded, gassed or went missing. Mount Olivet Cemetery is the final resting place of 12 known veterans who lost their lives in service connected deaths.

World War I officially ended on November 11th, 1918, known today as Armistice Day. When it was all said and done, almost 2,000 Frederick City residents had served their country in one way or another.

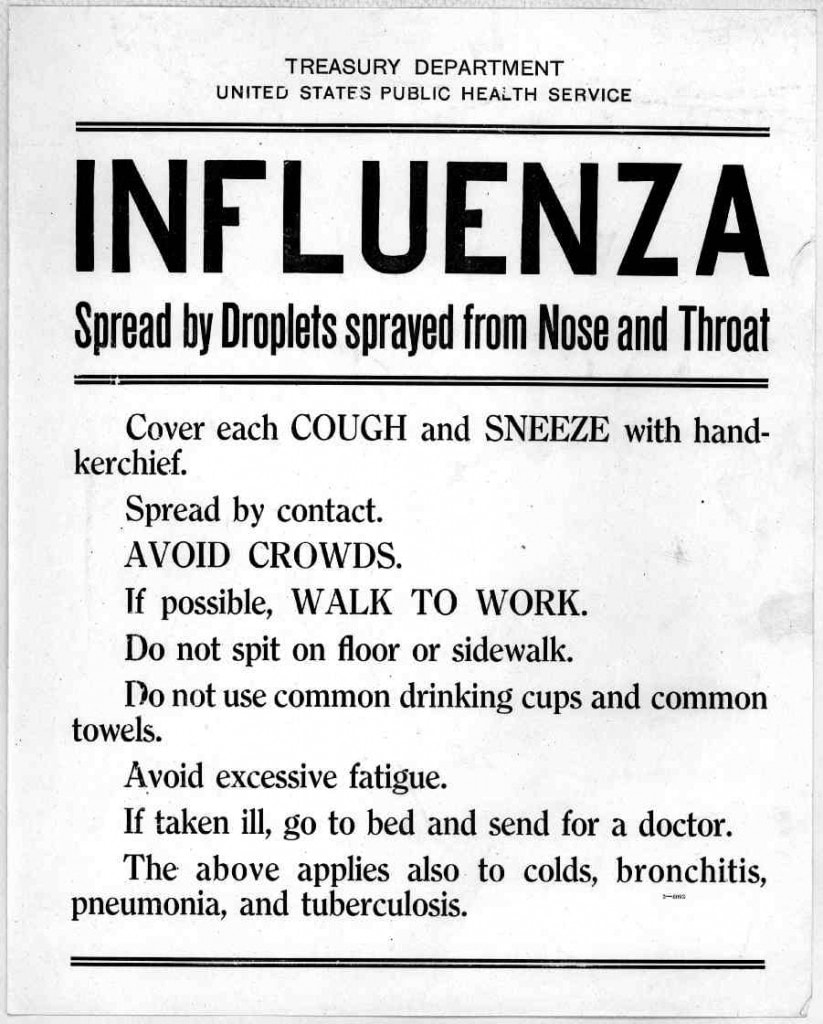

The Dreaded Flu

In 1918, the United States experienced a medical emergency like no other in its history. This came in the form of the Spanish Influenza, also known as the Great Flu Pandemic. Origins could be traced overseas to the American Doughboys serving in World War I. Many soldiers contracted the virus while living in the often cramped and wet conditions afforded that fall in the trench warfare being taken up in the Alsace-Lorraine region of France. Many soldiers would die, while countless others off the front lines, sending them back stateside to recuperate. In the process, the virus strain made its way to American soil.

The outbreak hit Frederick County in late September of 1918. Some 2,000 cases were reported. As if it wasn't enough to worry about loved ones fighting across the ocean, residents had to defend themselves here at home from getting sick. Cases would begin popping up throughout the county. One place hit hard was nearby Camp Meade, where local soldiers were training for duty in Europe. Mount Olivet Cemetery contains nearly 100 of the county's victims, and eight servicemen, some whom passed at the fore-mentioned Camp Meade. Two soldiers, Benjamin F. Eyler and William L. Dertzbaugh died of the flu in France, but their bodies were reburied in Mount Olivet a few years later.

In 1918, the United States experienced a medical emergency like no other in its history. This came in the form of the Spanish Influenza, also known as the Great Flu Pandemic. Origins could be traced overseas to the American Doughboys serving in World War I. Many soldiers contracted the virus while living in the often cramped and wet conditions afforded that fall in the trench warfare being taken up in the Alsace-Lorraine region of France. Many soldiers would die, while countless others off the front lines, sending them back stateside to recuperate. In the process, the virus strain made its way to American soil.

The outbreak hit Frederick County in late September of 1918. Some 2,000 cases were reported. As if it wasn't enough to worry about loved ones fighting across the ocean, residents had to defend themselves here at home from getting sick. Cases would begin popping up throughout the county. One place hit hard was nearby Camp Meade, where local soldiers were training for duty in Europe. Mount Olivet Cemetery contains nearly 100 of the county's victims, and eight servicemen, some whom passed at the fore-mentioned Camp Meade. Two soldiers, Benjamin F. Eyler and William L. Dertzbaugh died of the flu in France, but their bodies were reburied in Mount Olivet a few years later.

Stamp Act Repudiation mock- funeral in Courthouse Square (Nov. 30, 1765)

Stamp Act Repudiation mock- funeral in Courthouse Square (Nov. 30, 1765)

A Monument to the Troops

The swath of land in front of Frederick’s present day City Hall has always been an important meeting ground for over 270 years, dating back to the county’s founding in 1748. This was the location of Frederick's first brush with a European "super-power," and famous burial in county history-that of the British Stamp Act in late November, 1765. One week before, the Frederick County Court Justices repudiated the unpopular Act of Parliament, and the local Sons of Liberty thought it deserved the proper send-off by staging a mock-funeral.

As the former courthouse lawn, it once was surrounded by an iron fence, that is said to have helped corral pigs and other livestock. The citizenry begged for its removal around the turn of the 20th century, allowing for the public to enjoy the grounds more fully. Court Park, as it was briefly known, would become more commonly referred to as Court House Square (or Court Square).

In 1919, much discussion revolved around the removal of the decorative iron fountain located in front of the Courthouse front steps. This was a gift from resident James C. Clarke, a longtime railroad executive and namesake of Clarke Place on the city’s south side. Some wanted the iron fountain moved so a fitting World War I monument/memorial could be put in its place. Doughboy statues were going up in cities and towns throughout the country. One would be erected in Emmitsburg in the northern sector of Frederick County.

The swath of land in front of Frederick’s present day City Hall has always been an important meeting ground for over 270 years, dating back to the county’s founding in 1748. This was the location of Frederick's first brush with a European "super-power," and famous burial in county history-that of the British Stamp Act in late November, 1765. One week before, the Frederick County Court Justices repudiated the unpopular Act of Parliament, and the local Sons of Liberty thought it deserved the proper send-off by staging a mock-funeral.

As the former courthouse lawn, it once was surrounded by an iron fence, that is said to have helped corral pigs and other livestock. The citizenry begged for its removal around the turn of the 20th century, allowing for the public to enjoy the grounds more fully. Court Park, as it was briefly known, would become more commonly referred to as Court House Square (or Court Square).

In 1919, much discussion revolved around the removal of the decorative iron fountain located in front of the Courthouse front steps. This was a gift from resident James C. Clarke, a longtime railroad executive and namesake of Clarke Place on the city’s south side. Some wanted the iron fountain moved so a fitting World War I monument/memorial could be put in its place. Doughboy statues were going up in cities and towns throughout the country. One would be erected in Emmitsburg in the northern sector of Frederick County.